Feudal superiors, including barons, were also obliged to hold courts which administered the law and acted as a form of local parliament.[12]

The court involved itself with administration of the estate, ordained local laws, regulated the vassals’ behaviour, had the right of pit and gallows (to exercise trial and capital punishment) and could appoint officers ‘with what we would now recognise as legal authority and police powers’ such as baillies and sergeants.[13] Through his court and position at the head of society the baron ‘presided over most of the ordinary government and justice experienced by most of the people of Scotland during the medieval period’.[14] However, in serious cases the barony court was overseen by the local sheriff, and while the baron saw that justice was properly administered, he was legally, like his vassals, a litigant.[15]

As important as they were, we should not over-stress the legal aspects of the barony. Baronies were ‘fairly cohesive communities’ for the people within them; the tenants in a typical barony were disciplined through the barony court but they also used the barony mill and attended the barony’s parish church.[16]

In the words of Innes of Learney:

The Barony was a peaceful self-governing social unit… the economic functions of the Baronial-Council, or court, were far more important than its judicial functions… [and] the Barony was, like any other rural estate – only more so – both a co-operative and a communal unit.[17]

By the thirteenth century baronial jurisdiction was routine across the country.[18]

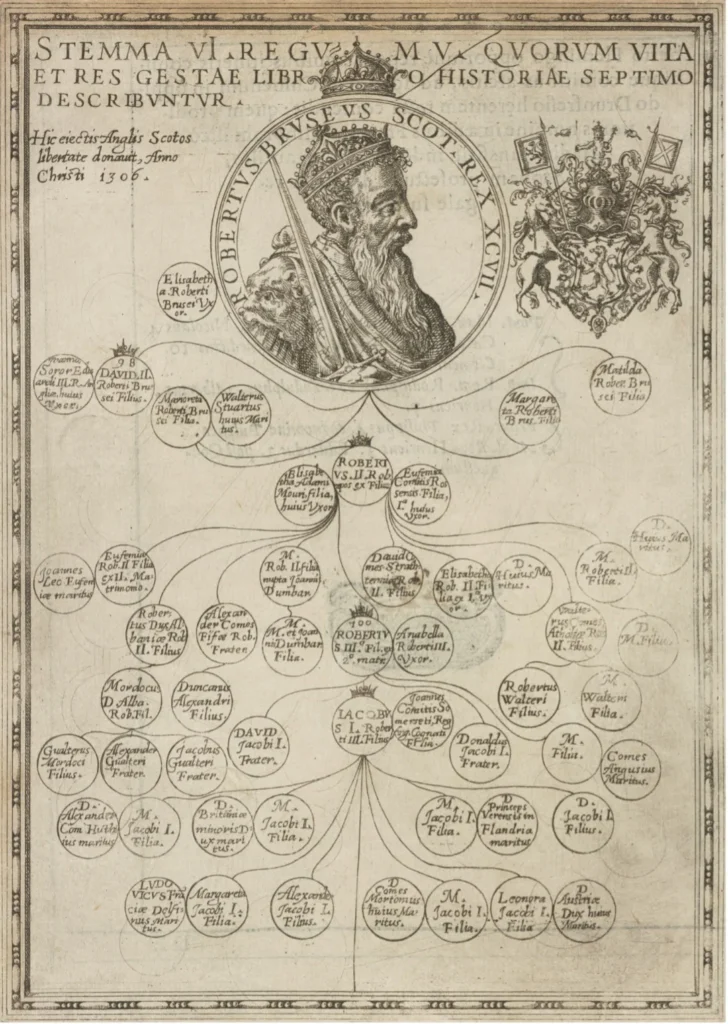

It is with the changes made by King Robert the Bruce in the early 1300s that we begin to see them more clearly in the records. With his coming to power the new king punished those who had sided against him during the Wars of Independence and rewarded his followers, meaning many baronies changed hands. Robert also developed the rights of the barons, restricting baronial jurisdiction to estates which the crown permitted to be held ‘in free barony’. This is a title, where land is erected in liberam baroniam, as a temporal fief for the baron.[19] The erection of an estate to the status of liberam baroniam distinguished it from an estate held merely as a tenancy-in-chief of the king.

The holder of an estate in liberam baroniam became a baron, vested with certain rights whereas other holders were lairds with neither title nor nobility. However, the historian Alexander Grant believes that although only a minority of baronies were held ‘in free barony’ it is likely that within the remaining ‘ordinary’ baronies barons still exercised their judicial and administrative functions.[20]

Overall, the number of baronies was reduced but there were still over 200 at the end of Robert’s reign and they continued to be granted by the Crown so that they had increased to some 350 by 1400.

While in the fourteenth century most barons were in practice local lairds, from the twelfth century onwards powerful barons held several baronies or were important in other ways.[21]

There was no clear line between these ‘greater barons’ and the others, and it seems a baron could move in and out of this ‘second rank’ of the upper nobility.[22] The pressure grew from the greater barons for a way of distinguishing themselves from the ‘lesser’ barons.[23] From the 1440s the Scottish peerage began to emerge within the higher nobility, with greater barons becoming lords of parliament, the peerage’s bottom rank beneath the dukes, earls and provincial lords. These lords of parliament adopted the English parliamentary ranks in their naming systems and in the right to summonses to parliament. This institutionalised the higher nobility into an easily identifiable group, the lords rather than the ‘lairds’.[24]

The centrality of all baronies to Scottish society, no matter the status of their holder, continued. In 1426 King James I decreed that all lords, meaning barons, with lands in northern Scotland were to maintain their castles properly for better governance and policing. King James IV in 1496 ordered that all barons send their eldest sons to grammar schools and universities, so they understood the laws of the realm. Most of the land in Scotland in the fifteenth century was held in liberam baroniam, including the larger baronial jurisdictions such as lordships and earldoms.

Baronies were becoming more complex. In many places the trend was to split up individual baronies or amalgamate them, and the Crown continued to create new ones.[25] By the sixteenth century there were over 1000 baronies, though these were more fragmented than before and not always representing a geographically continuous area as they had once done.[26]